In the intricate tapestry of nature, few biological substances command as much fear and fascination as 毒液. These complex cocktails of proteins and peptides have evolved over millions of years as sophisticated weapons for hunting and defense. Beyond their role in the wild, venoms hold remarkable potential for human medicine, offering solutions to some of our most challenging health problems.

目录

切换Types of Venom: Nature’s Chemical Arsenal

Venoms are not all created equal. These biochemical marvels have evolved along different pathways to target specific physiological systems in prey or predators. Understanding these distinctions helps scientists harness their potential for medical applications.

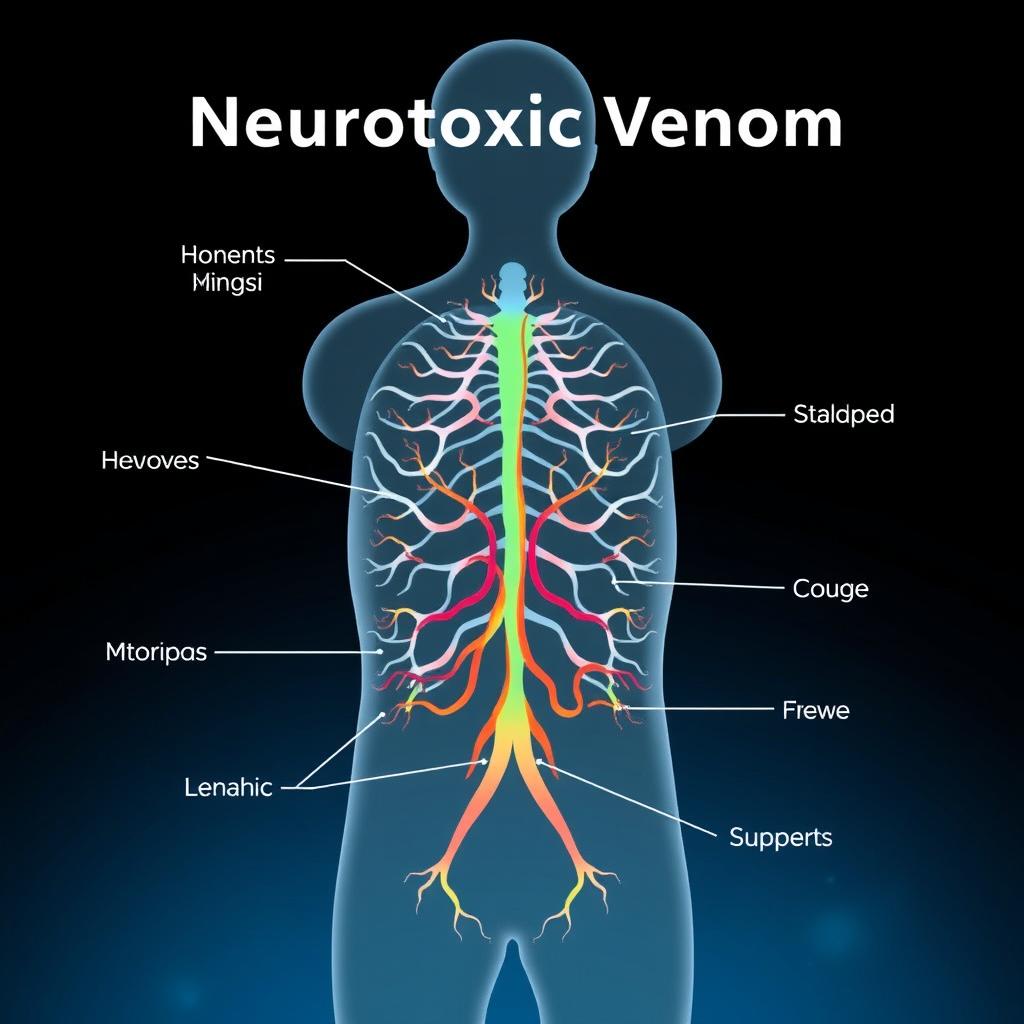

神经毒性毒液

Neurotoxic venoms target the nervous system, disrupting nerve impulse transmission. These venoms can cause paralysis, respiratory failure, and even death. Common examples include those from cobras, mambas, and many marine creatures like cone snails.

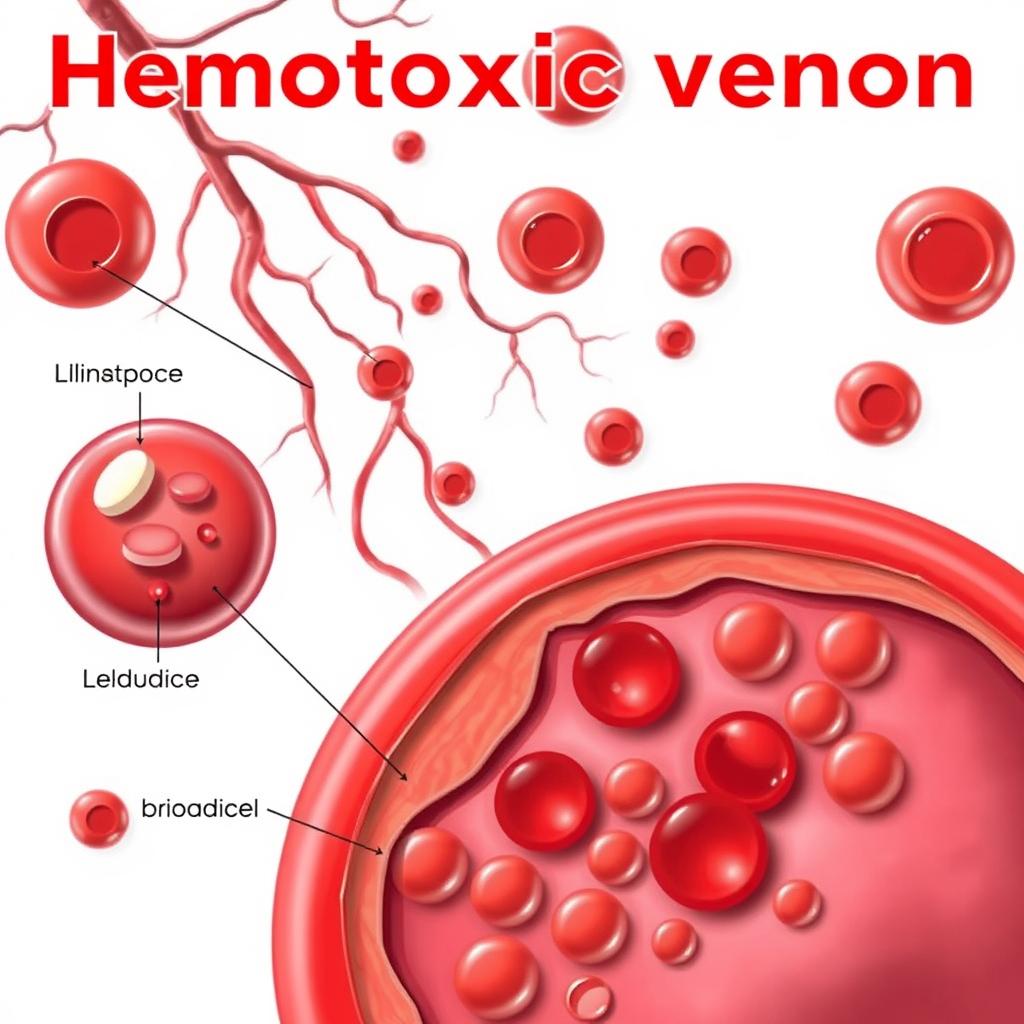

血液毒性毒液

Hemotoxic venoms attack the cardiovascular system, destroying red blood cells, disrupting blood clotting, and damaging blood vessels. Vipers like rattlesnakes and cottonmouths primarily deploy these venoms, causing tissue damage and internal bleeding.

细胞毒性毒液

Cytotoxic venoms destroy cells and tissues on contact. These venoms, common in spitting cobras and some spiders, cause necrosis, tissue death, and permanent scarring. The damage is often localized but can be severe and disfiguring.

A 2022 study published in Nature Communications identified over 14,000 unique toxin molecules across venomous species, with potentially thousands more awaiting discovery. Each venom contains between 20-100 different compounds working in synergy.

Remarkable Venomous Creatures

The animal kingdom hosts an astonishing array of venomous species, each with unique adaptations and venom compositions. These evolutionary marvels have developed their toxic arsenals over millions of years.

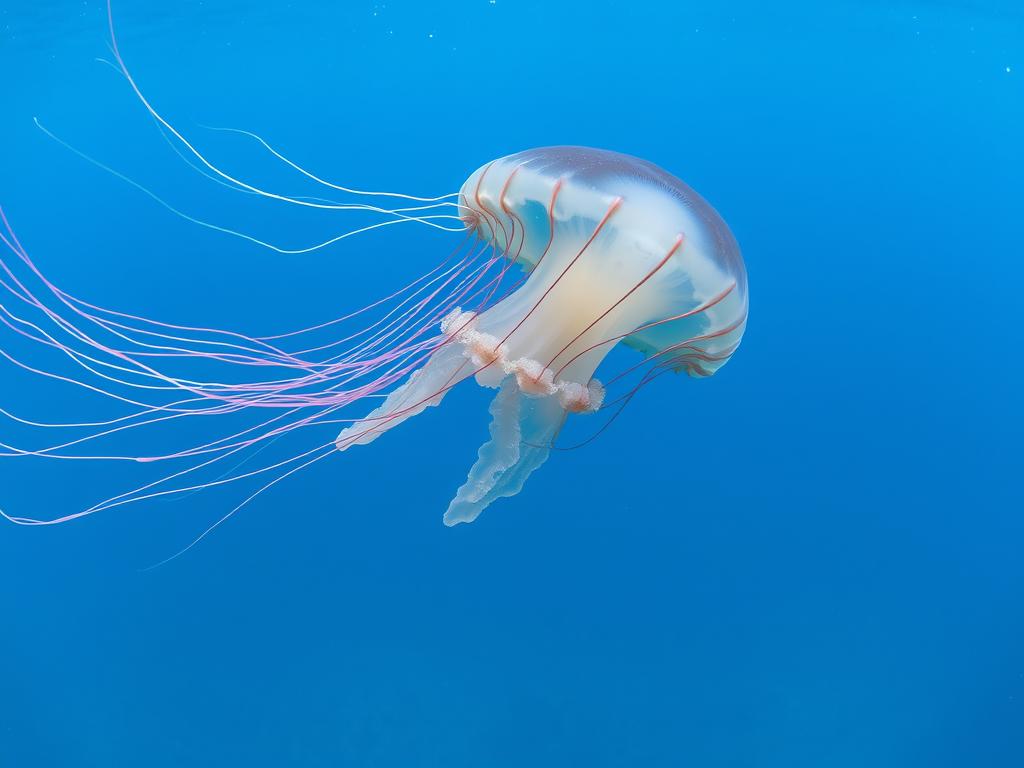

Box Jellyfish

The box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) possesses one of the most potent venoms known to science. Its tentacles contain millions of nematocysts (stinging cells) that can cause cardiovascular collapse within minutes. Remarkably, recent research has identified compounds in box jellyfish venom that show promise for treating cardiac conditions.

Inland Taipan

The inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) delivers the most toxic venom of any land snake. A single bite contains enough venom to kill 100 adult humans. Native to Australia, this snake’s venom has evolved to rapidly immobilize small, warm-blooded prey. Scientists are studying its unique neurotoxic properties for potential treatments of neurological disorders.

Cone Snail

The unassuming cone snail harbors a sophisticated venom delivery system—a modified tooth that acts as a harpoon. These marine mollusks produce conotoxins, highly specific compounds that target the nervous system. A 2023 breakthrough identified a cone snail peptide that can block pain signals without addiction risks, unlike opioids.

Gila Monster

The Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) is one of few venomous lizards. Its venom contains exendin-4, which led to the development of Byetta, a medication for type 2 diabetes. This remarkable translation from venom to medicine demonstrates how nature’s toxins can become therapeutic treasures.

Blue-ringed Octopus

The tiny blue-ringed octopus carries enough tetrodotoxin to kill 26 adults. This powerful neurotoxin blocks sodium channels in nerve membranes, causing respiratory paralysis. Despite its lethality, researchers are investigating modified versions of this toxin for use as local anesthetics and pain management tools.

Venom in Medicine: From Deadly to Healing

The transition from feared toxin to therapeutic agent represents one of the most fascinating chapters in medical research. Venom components are being transformed into life-saving medications across multiple fields of medicine.

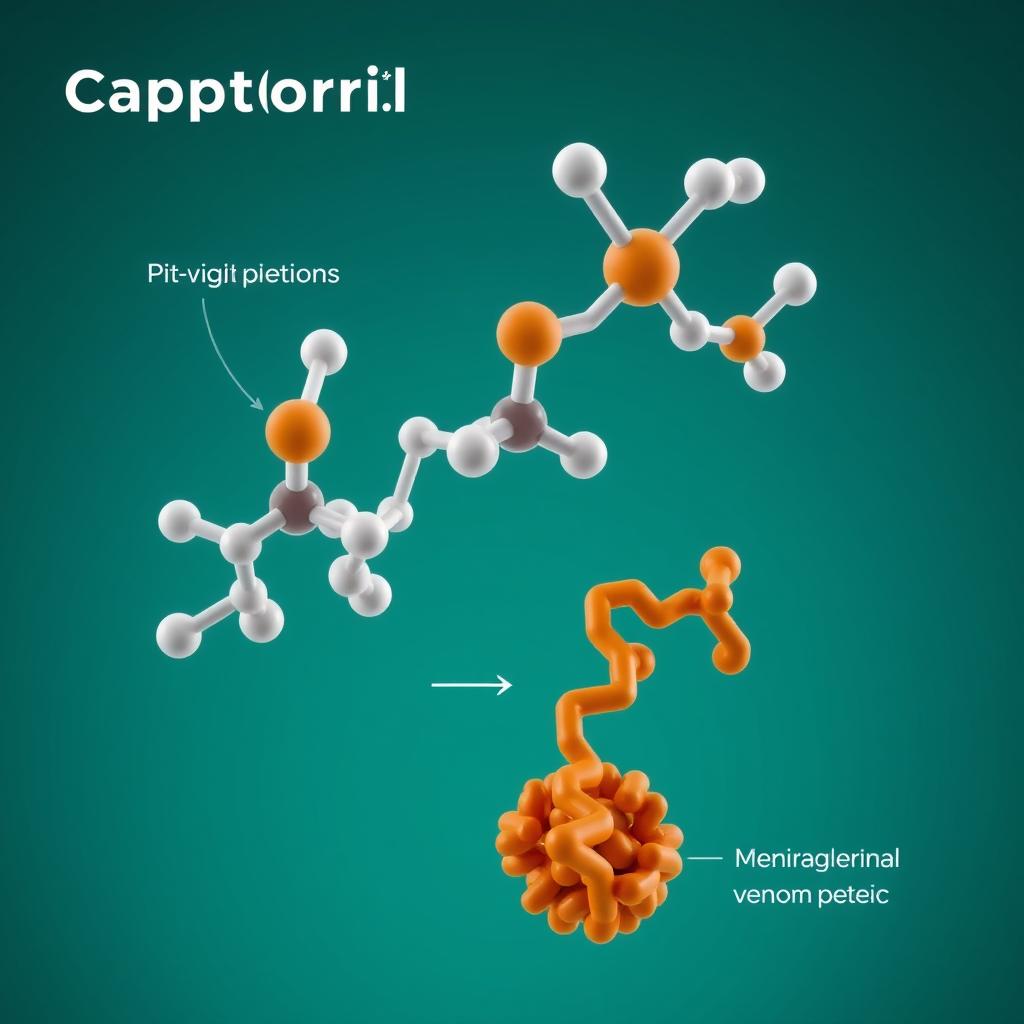

Cardiovascular Medications

The first FDA-approved venom-based drug was captopril, derived from the Brazilian pit viper. This ACE inhibitor revolutionized hypertension treatment. Today, researchers are investigating tarantula venom peptides that can repair damaged heart tissue following heart attacks.

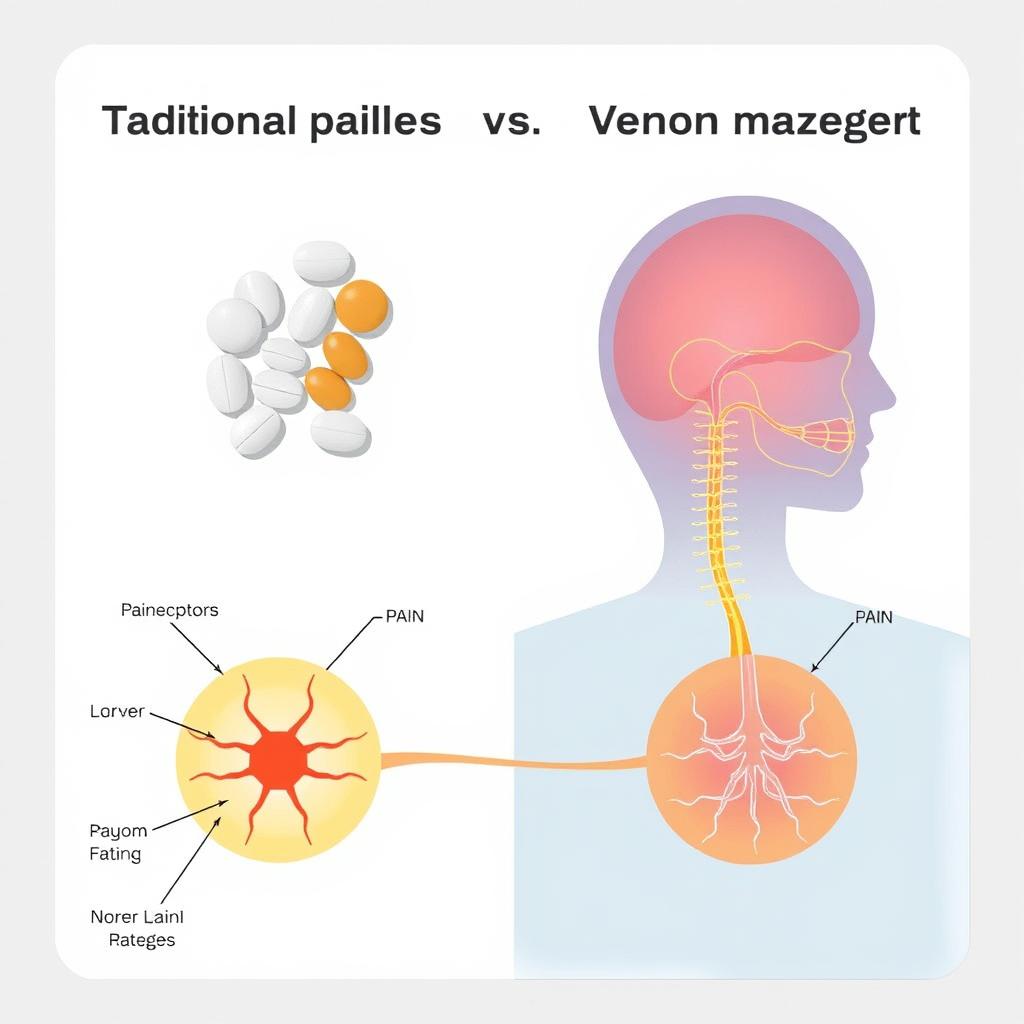

Pain Management

A 2021 study in Nature Neuroscience identified a sea anemone toxin that targets specific pain channels without affecting other sensations. Unlike opioids, these venom-derived compounds don’t cause addiction or respiratory depression, potentially offering safer alternatives for chronic pain sufferers.

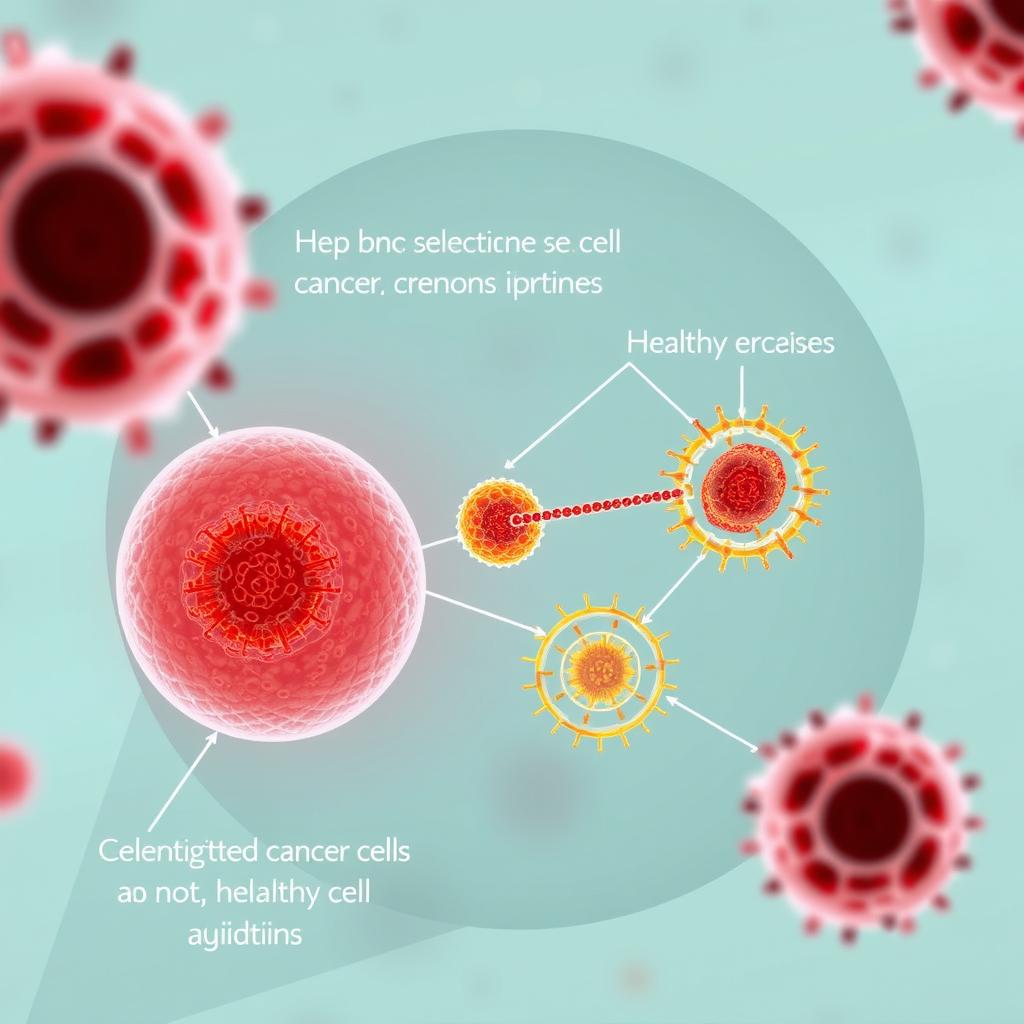

Cancer Treatment

Researchers at the University of California discovered that chlorotoxin from deathstalker scorpion venom can bind specifically to brain cancer cells. This property is being used to develop targeted drug delivery systems and imaging tools that can distinguish between healthy and cancerous tissue with unprecedented precision.

“Venoms represent one of nature’s most refined pharmacopoeias. Each toxin has been perfected through millions of years of evolution to target specific physiological pathways with remarkable precision.”

Survival Guide: Staying Safe Around Venomous Creatures

While venomous animals rarely attack humans unprovoked, encounters do happen. Understanding prevention and proper first aid can make the difference between life and death.

Prevention Tips

- Be aware of your surroundings, especially in wilderness areas known for venomous species.

- Wear appropriate protective clothing such as closed shoes, long pants, and gloves when in high-risk environments.

- Never handle unknown animals, even if they appear dead. Many venomous creatures can still envenomate after death.

- Use a flashlight when walking at night in areas with venomous snakes or scorpions.

- Keep living spaces clean and free of debris that might attract venomous creatures.

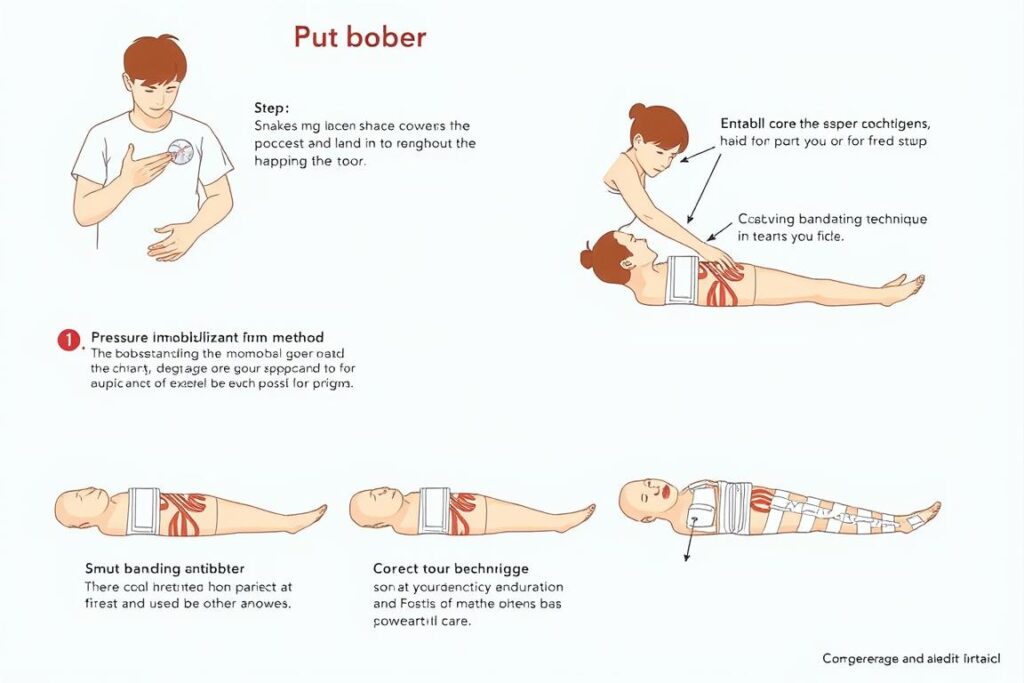

First Aid Essentials

- Move away from the animal to prevent additional bites or stings.

- Keep the affected area immobilized and below heart level if possible.

- Remove jewelry or tight clothing near the bite site before swelling occurs.

- Clean the wound gently with soap and water if available.

- Do NOT cut the wound, apply a tourniquet, suck out venom, or apply ice.

- Seek medical attention immediately, even if symptoms seem mild initially.

Important: Different venomous bites require different first aid approaches. For example, pressure immobilization is recommended for neurotoxic snake bites but may worsen tissue damage from cytotoxic venoms. Always follow region-specific guidelines and seek professional medical help as quickly as possible.

Venom in Culture and Mythology

Throughout human history, venomous creatures have slithered, crawled, and swum through our collective imagination, shaping cultural narratives and symbolic systems across civilizations.

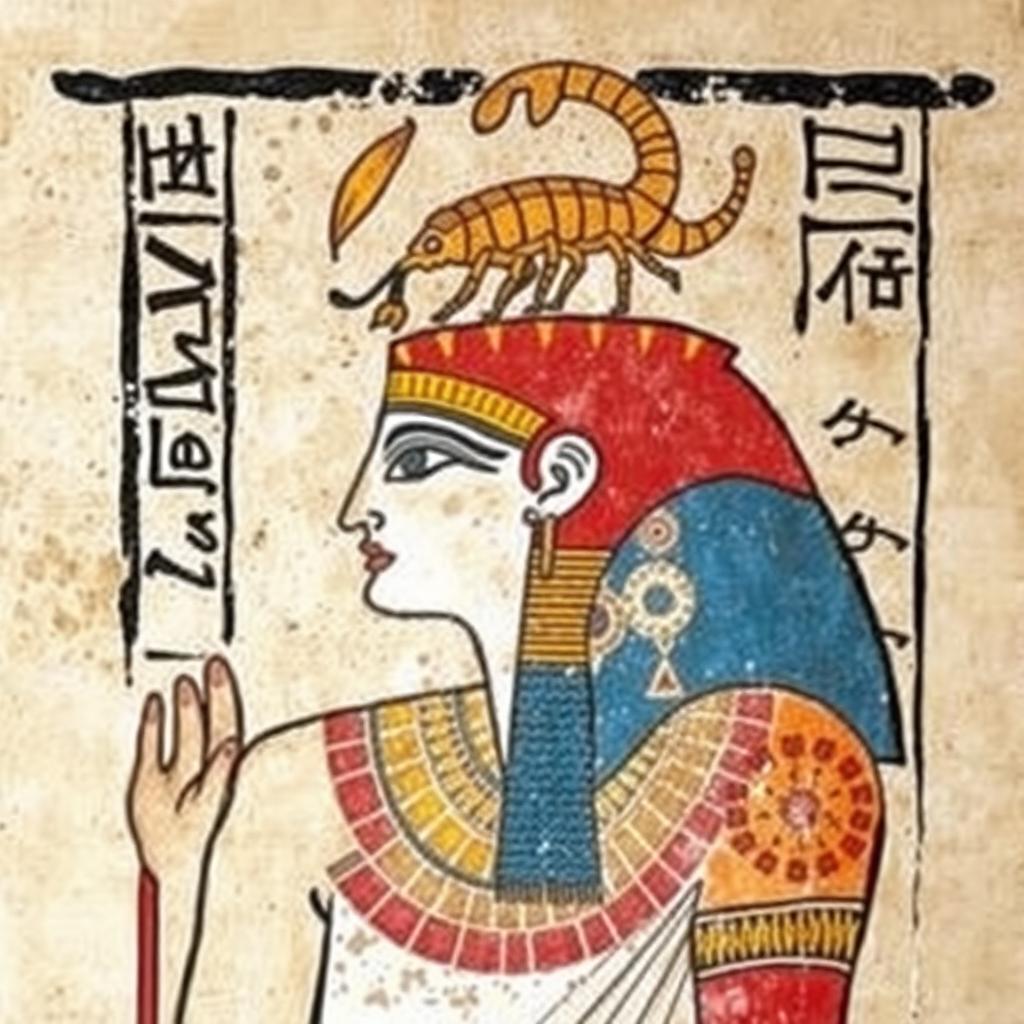

Ancient Mythology

In Egyptian mythology, the goddess Serket was associated with scorpions and healing venomous stings. Similarly, Greek mythology featured the Hydra, a serpentine water monster whose venom was so potent that even its breath was deadly. These mythological beings reflected humanity’s ancient understanding of venom’s power.

Cultural Practices

Some cultures have developed unique relationships with venomous creatures. The Irula tribe of India are renowned snake catchers who help produce antivenom. In certain religious practices, controlled exposure to venomous snakes represents faith and divine protection.

Modern Pop Culture

In contemporary media, 毒液 has inspired characters like Marvel’s anti-hero Venom, a symbiotic alien with fluid-like abilities and fearsome appearance. This character embodies the dual nature of venom itself—dangerous yet potentially beneficial when properly harnessed.

Frequently Asked Questions About Venom

Yes, many venoms are specialized to target specific prey and have little effect on humans. For example, most tarantula venoms cause only mild reactions in humans despite being lethal to insects. Additionally, the quantity of venom injected matters—many venomous animals can control their venom output or deliver “dry” bites without venom.

Venom is actively injected through specialized structures like fangs or stingers, while poison is absorbed, ingested, or inhaled. Simply put: if it bites you and you get sick, it’s venomous; if you bite it and you get sick, it’s poisonous. Some animals, like certain frogs, can be both venomous and poisonous.

While complete immunity is rare, some individuals can develop increased tolerance through repeated low-dose exposure. This principle is used in immunotherapy for certain venomous stings. However, self-immunization is extremely dangerous and potentially fatal. Additionally, venom composition can vary even within the same species, making true immunity virtually impossible.

Antivenom production typically involves injecting diluted venom into animals (usually horses or sheep) whose immune systems produce antibodies against the venom components. These antibodies are then harvested and purified to create antivenom. Modern research is exploring synthetic alternatives to reduce reliance on animal-derived antibodies.

The Future of Venom Research

As we continue to unlock the secrets of nature’s most potent biochemical cocktails, venom research stands at the frontier of medical innovation. From pain management to cancer treatment, these once-feared substances are becoming valuable tools in our therapeutic arsenal.

The venomous creatures that have evolved these remarkable compounds deserve our respect and protection. Many species face threats from habitat loss, climate change, and direct persecution based on fear rather than understanding.

Help Protect Venomous Species

Venomous creatures play crucial ecological roles and hold untapped potential for medical breakthroughs. By supporting conservation efforts, you can help ensure these remarkable animals continue to thrive—and that their life-saving secrets remain available for future generations.